- GOLDA

- Posts

- For Persian Jews, the Iran Protests are Personal

For Persian Jews, the Iran Protests are Personal

Tannaz Sassooni and Rachel Sumekh share their hopes and fears about what may come of the massive uprising

A lot of us can’t look away from the historic uprising—and brutal crackdown—happening in Iran right now. But for the Iranian Jewish community here in the U.S., the events of the past week are deeply personal.

In 1979, after the Shah of Iran was overthrown and the Islamic Republic was installed, the country’s Jewish population—which had been there since the days of ancient Persia, as you might remember from the Purim story—faced increasing persecution and violence. Many families left everything behind and fled, either to Israel or the U.S., and were never able to return.

Iranian Jews largely settled in two places once they got to America: Los Angeles and Great Neck, NY. I grew up in Great Neck, where I had a front-row seat to this vibrant immigrant community’s American chapter. Iranian Jews (also known as Persian Jews) are really their own hyper-specific category–not entirely captured by our broad classifications of Ashkenazi, Sephardi, or Mizrahi.

The Persians I grew up with did everything big. After school at their houses we would eat homemade saffron rice out of catering-sized trays, leftovers from a casual family dinner. At the end of bar and bat mitzvah services the Persian families would ululate in celebration and throw hard candy at the bimah (which, I can personally attest, hit harder than the Sunkist Fruit Gems we Ashkenazim threw). It was a culture filled with music, dancing, food, and life, despite—or perhaps, in spite of—their abrupt geographic dislocation.

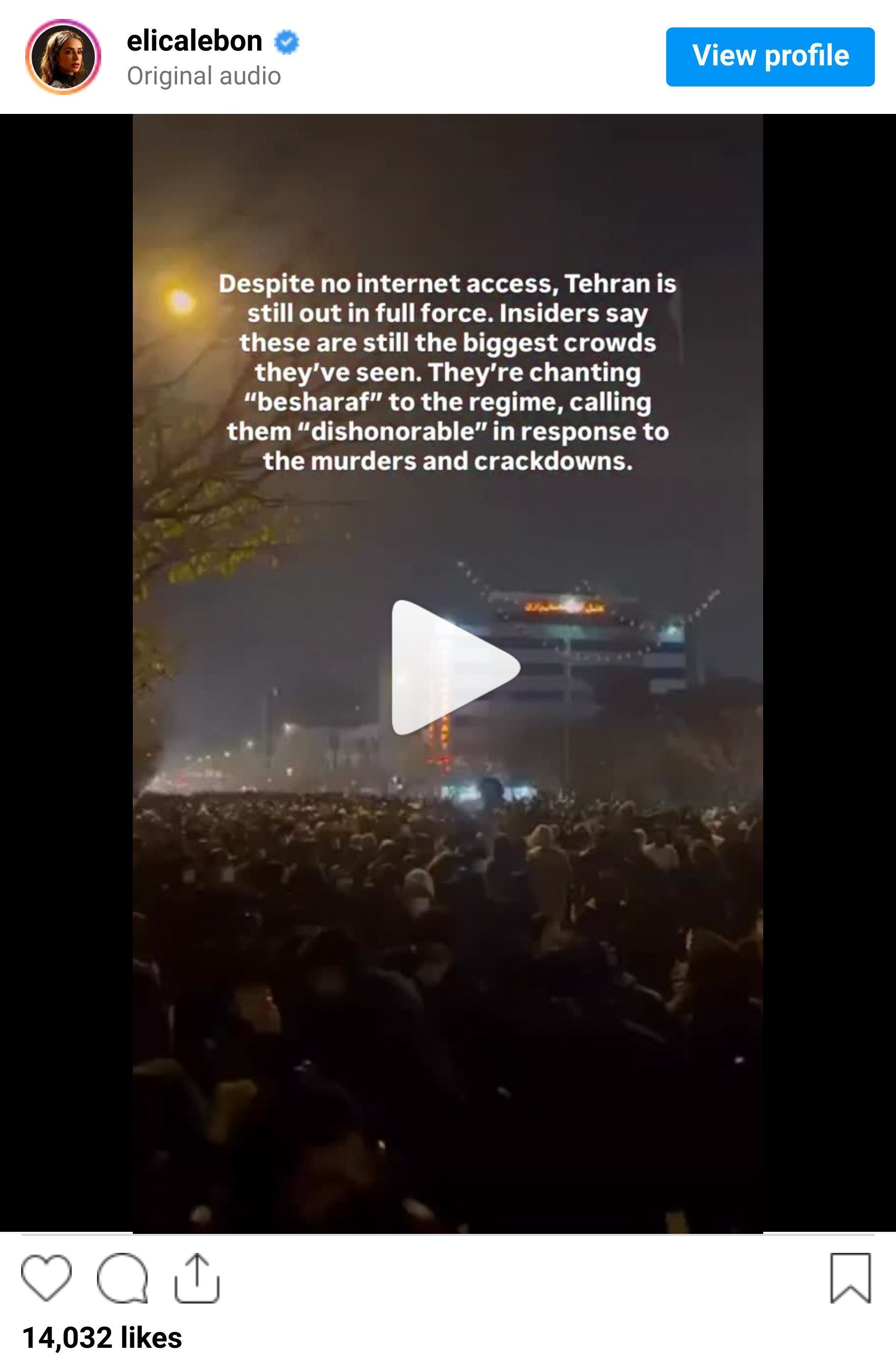

Today’s uprising is against that very same oppressive regime the Jews fled nearly five decades ago, and Iranian Jews here in the U.S. have been taking to social media to share updates and offer context.

I caught up with two of my favorite Iranian Americans, food writer Tannaz Sassooni and entrepreneur and anti-hunger activist Rachel Sumekh, to see how they were navigating the news of the past week. They graciously shared all that and more—including a delicious Persian recipe—in our conversation below.

Tell me about your own families’ journey to the U.S. When did they leave Iran, and under what circumstances?

Tannaz: This is a long story, but I’ll try to abridge! In January 1979, I was about 16 months old and my sister was 7 years old. We were visiting my grandparents in Tehran (we lived in Shiraz at the time). In the thick of the revolution, the airports were closed, but El Al was still servicing a single flight a day from Tehran to Tel Aviv. My dad was able to book that flight for my mom, my sister, and I to just get out, and we left the next day. After a few weeks on relatives’ couches in Israel, we came to the U.S. My dad stayed to work until it was no longer safe for him to be there, and in 1982 he crossed the country on land, was able to make his way into Turkey, from there to Tel Aviv, and then to Los Angeles. None of us has been back since.

Rachel: My mom was 22 when a friend knocked on her door and said, “I found a smuggler—we’re leaving tomorrow.” They drove to the border and traveled by camel until they reached Afghanistan. With help from HIAS, my mom resettled in Israel. It was the early–mid ‘80s, when the U.S. had tightened its borders against Iranian refugees. Once the rumblings of revolution began, the regime allowed no one to leave Iran.

My dad left before the revolution and at age 18 arrived in Stillwater, OK, where he did his undergraduate and graduate studies in engineering. They met in the late ‘80s when my mom visited LA and they got married two months later. Both families left tons of property behind to find lives of freedom.

How did the legacy of the Iranian Revolution shape your families?

Tannaz: The legacy of the revolution shapes everything about our family. Our extended family, once all in one or two cities, is now scattered across the globe, but we remain deeply connected. The culture inside our home growing up was far more driven by our Iranian heritage than our American neighbors’.

Rachel: It still shapes us. We hold tightly to the traditions we brought with us, and I think we’re still answering the question of what our legacy in the U.S. will be.

On my social media feeds I’m seeing a lot of posts from Persian Jews about the protests happening in Iran. What kind of feelings does this news raise for you?

Tannaz: There have been so many false starts over my life that it’s hard to let myself hope, but my heart breaks for the violence that the utterly cruel Islamic Regime is inflicting on the people of Iran, and I remain, as always, in awe of their courage. I’m watching intently.

Rachel: Earlier this week, I dreamt that my family and I flew to Iran. The revolution was still happening, but there was a sense of peace…like change was on the way. I walked into a wannabe Starbucks whose only menu item was Persian tea, haha. It was long and beautiful, all in muted colors. I think many of us post with that dream of being in Iran in mind. But we are still in the early stages of revolution, which is bloody and heartbreaking. We pray for our Iranian cousins marching with their lives on the line.

Most of the Iranian Jews I knew growing up described themselves as Persian. Can you explain that difference?

Tannaz: Persian is our language, but some prefer to use it as our ethnicity as well, as it separates them from the regime and all the horrible things it’s associated with. In everyday conversation, I use them interchangeably – people are often more used to hearing Persian, so I tend to have to explain myself less with that. But Iranian is technically correct, and that’s what I use in my writing.

Rachel: Persian is an ethnicity; Iranian is a nationality. There are dozens of ethnicities in Iran, Persian is just one. Using “Iranian” in this moment is also more inclusive of Kurdish Iranians, Azerbaijani Iranians, and others who aren’t Persian. Building on what Tannaz said, the terms have shifted with political moments. For example, after the 1979 hostage crisis, many in the diaspora used “Persian” to distance themselves from Iran.

What is distinct about Persian Jewish culture (and perhaps LA Persian Jewish culture!) from the rest of the diaspora?

Tannaz: It’s such a small, connected community that everyone feels like family (and probably are!). There is a shared rhythm to the year that comes from celebrating not only Persian holidays like Norouz and Yalda, but also Passover and the High Holidays. We have Shabbat, and for Iranians, the eve of Shabbat is a sacrosanct night of family togetherness and feasting (usually with dishes like gondi and chelo nokhod ab).

Rachel: Iranian Jews are a double diaspora; our rituals are all an ode to different worlds and lands. While we had Jewish traditions, judaica, languages etc for thousands of years, in the States we were met with American and Ashkenazi Judaism. I know more Debbie Friedman tunes than I do Mizrahi tropes. Our Judaism today is a fusion of what we came with and what we’ve learned from other Jewish cultures.

Tannaz, you explore Iranian Jewish culinary traditions in your work as a food writer. Is there a hunger among young Persian Jews to preserve those recipes and rituals? (And is there a recipe you could share to accompany the interview!)

Tannaz: There is! Our moms and grandmas received these recipes orally, so sometimes it’s hard to get concrete recipes from them – the recipes live in their hands. So to have exact measurements, and a trove of regional recipes that are new to many is a real boon. And these days, it’s not just limited to women! There are plenty of Iranian Jewish men who make a mean tahdig.

In honor of Iran, I’ve included a kabob recipe below.

The two of you created Erev Yalda, a new take on the ancient Persian celebration of the winter solstice. Tell us about bringing this tradition to life for a new audience, and what we can all learn from Yalda, as well as Iranian Jewish tradition more broadly.

Tannaz and Rachel: Yalda asks us to sit with dark places instead of fearing them. We stay up late with loved ones on the year’s longest night, bonding over rich poetry and delicious foods, settling in and finding new insight from this darkness. Bringing our Persian and Jewish traditions together, and finding so much beautiful overlap, was a good reminder that there is so much more that unites us than divides us. It’s a crucial message today.

Tannaz’s Jujeh Kabob Recipe

Makes 4 servings

Chelo Kabob, grilled meat with basmati rice, is Iran’s national dish. Jujeh kabob, the variation with grilled chicken, usually requires marinating the chicken in a tangy saffron yogurt mixture. Since that isn’t kosher, Iranian Jewish revise the recipe, getting the acid and tenderizing function from copious lemon juice.

Traditionally, Iranian kabob is grilled on long, wide metal skewers. You can do it with small wood skewers, but it may be a good idea to use two side-by-side, especially for the heavy tomatoes.

Ingredients:

⅓ cup lemon or lime juice

Pinch of saffron

1 tsp salt

1 tsp ground black pepper

¼ cup olive oil

4 boneless skinless chicken breasts, cut into 2 inch pieces

1 medium onion, peeled and cut into 8 wedges

4 Roma tomatoes

Step 1: Marinate the chicken

Add lemon or lime juice to a medium bowl. If possible, grind saffron into a fine powder in a mortar and pestle, using a few grains of sugar for extra abrasion. Add saffron to bowl and stir to combine – the juice should start to take on an orange yellow color. Add salt, pepper, and olive oil, and stir again. Add chicken pieces and onion wedges, stir to coat all of the chicken in the marinade. Cover and refrigerate for at least an hour or two, preferably overnight.

Step 2: Prepare skewers

Set your grill to high. Build skewers alternating chicken and onion pieces. (Alternatively you can grill the onion on separate skewers.) Place tomatoes on separate skewers, using two skewers about an inch apart.

Step 3: Grill

Grill chicken, turning it occasionally, until the outside is golden brown, with perhaps a bit of char, and when you cut into a piece, the flesh is white (not pink), and the juices run clear.

Grill tomatoes until the skin starts to char, and the tomatoes are warmed through and softened.

Keep cooked food in a platter covered with a piece of foil to keep it warm until ready to serve.

Step 4: Don’t forget the accoutrements

Copious steamed basmati rice or Persian style steamed rice with tahdig is an essential accompaniment. You can fill your kabob spread with flatbread such as sangak or lavash, a platter of fresh herbs (such as basil, tarragon, mint, and radishes), your favorite pickled vegetables, and a Shirazi salad.

I’m grateful to Tannaz and Rachel for sharing their stories. It’s a powerful reminder of what’s at stake in Iran today, and the bravery of the protestors.

Stay GOLDA,

Stephanie

Reply